Poetree offers fruit year round at 10th and Lincoln in TD

Walk of the Town: the “Poetree”

A series inspired by yards & the art of walking

By Sarah Cook

On the corner of 10th and Lincoln streets, about 8 blocks from my house, stands a small cedar box perched atop a 4-foot snag. An understated piece of wood affixed to the very top bears one word, in stenciled white letters that trail at the ends as if to highlight where the hand that painted them began and finished its work: “Poetree.”

There are no two ways about it: it’s a cute pun. A gift given to retired hospice RN Colleen Ballinger approximately six years ago, this piece of personal art, fused with nature, beckons walkers and bikers, young and old alike to take a poetic pause along their daily route and engage with something beautiful.

Though poetry gets its own month (every April!) and people can usually name at least one poet or poem that they hold dear, poetry’s ancillary existence alongside other genres—mainstream fiction, mystery paperbacks, self-help books—creates in me big feelings of surprise and affinity when I encounter someone else with an active, daily relationship to the form. The Poetree, an early landmark for my partner and I as we were getting our sea legs in The Dalles, made an immediate and lasting impression on me.

As with the best moments of inspiration, the Poetree was born out of a convergence of many things. Colleen and her family often marveled at the existence of all kinds of poetry boxes and yard displays in the Portland area; during the same span of time, she belonged to a writers group where a poet introduced her to the existence of National Poetry Month. And so on the following mother’s day, her husband and daughter collaborated on a gift that would become a turning point in Colleen’s own creative work.

“It has helped me to process things when I’ve submitted my own stuff,” Colleen states about her occasional contributions, which change in response to seasons and current events and depending on the amount of work she receives from others, including strangers. She shares, for example, the experience of processing her sister’s death about a year ago: “Her parting words were, ‘whenever you see a butterfly, think of me.’” In equal parts memory and celebration, Colleen featured an image alongside a quote from late Glee actress Naya Rivera: “Butterflies can never see the beauty in their own wings.”

In addition to her own contributions, Colleen describes a variety of work submitted by friends, neighbors, and people she doesn’t know. There’s the teacher who’d been working with a young non-native speaker and approached Colleen, asking if she could submit a poem written in English by the 12-year-old girl. Or there was the winter where, on the first day of snowfall and as Colleen was approaching her car, she looked over to see, rolled up in ribbon, a new submission. Untying the ribbon, she discovered a poem about snow and winter. The pleasure of encountering this particular submission on this particular day has stayed with her — how could the author have managed such timing? To this day, she doesn’t know who the submission came from.

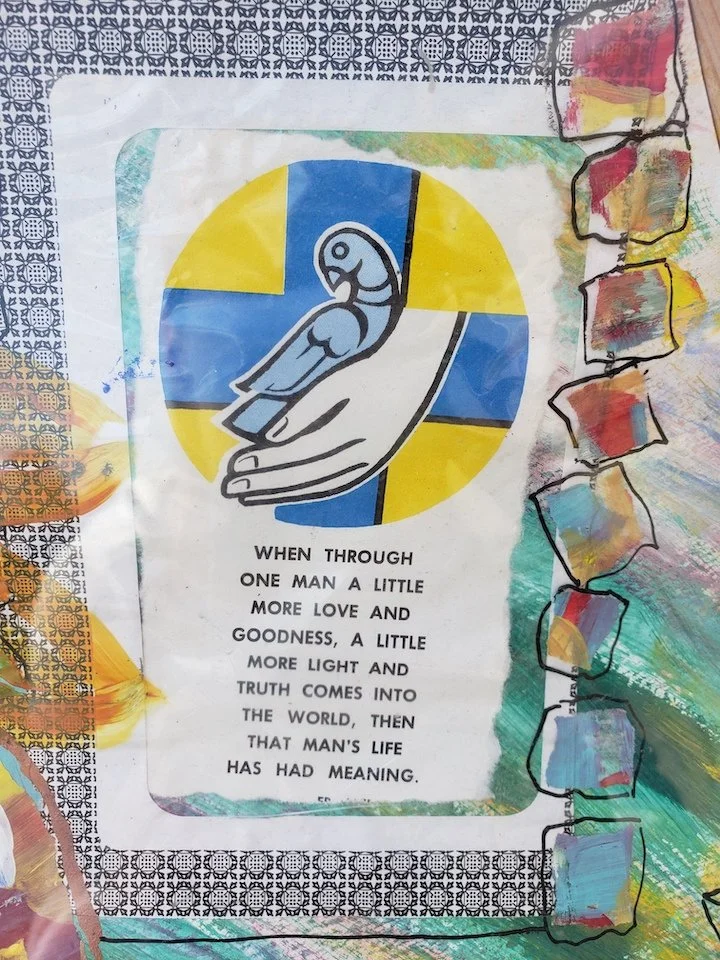

The Poetree has served as a beacon not only during personal hardships but global ones as well. The current feature is in response to the war in Ukraine, exacerbated by the fact that Colleen has family living in Poland. While she speaks with clarity about her motivations behind the piece, she also shares the kismet details of how it came together.

While cleaning out some of her old belongings, Colleen found a copy of the Catholic holy card that had been passed out at her grandfather’s funeral. She was immediately moved by the resonance between the quote—a few lines about what it means to be a strong man—and the situation in Ukraine. She took the verse back to an image she’d recently been working on, some abstract black marks near the bottom of a page with a randomly drawn sunflower. It was then that everything clicked into place: recalling the recent viral video of the Ukrainian woman insisting that a Russian soldier put sunflower seeds in his pockets, “so at least sunflowers will grow when you all lie down here,” Colleen saw the connection between her hastily drawn sunflower, her grandfather’s quote (which speaks to, as Colleen puts it, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s admirable strength), and those small black marks sitting at the flower’s base and looking, as a matter of fact, a lot like tombstones.

The art that Colleen produces for the Poetree increasingly utilizes mixed media (in short: artwork that embraces collage and a variety of materials and mediums—paint, magazine clippings, decorative tape and other paper ephemera, etc.). But this wasn’t always the case. About a year ago, Colleen took an art class through Zoom with locally beloved artist and gratitude ambassador Jenny Loughmiller. “It was outside my comfort zone,” states Colleen, who “couldn’t imagine doing art online like that.” She goes on to describe, however, “the freedom I felt not being in a room with other artists but being in my own space, learning from [Loughmiller],” and how the techniques of mixed media “totally freed me—because I’m such a rule follower.” This breakthrough has led to what can only be described as a reinvigorated relationship to her experience of creativity: the deep and necessary connections between image and word, between art and healing, not to mention a broader understanding of what the Poetree can provide.

The experience of struggling within the digital realm as it limits, shapes, and informs the IRL or AFK one (“in real life” and “away from keyboard,” respectively) is the struggle most of us have faced during the pandemic years. That her experience continues to manifest in the form of a physical vessel, quaint yet assertive, where poetry and art converge in a burst of free and open-hearted messaging, is a testament to what can happen when our coping strategies exist in close proximity with our creativity, and the resiliency that, as a result, often blooms.

There was one question I had in mind going into my conversation with Colleen that didn’t come up organically prior to my asking it: I wanted to know about her relationship to yards and playing outdoors as a kid, and if and how this might inform her current relationship with her yard and, specifically, the Poetree.

Tulips cresting over a sea of groundcover.

“My dad was in the military and we moved every two years,” she shares, expressing so much enthusiasm for my question that I can hear her smiling through the phone. “When I was in 2nd through 5th grade, we lived in Panama. It was like perpetual summer there—we were outdoors playing all the time. We had iguanas, all kinds of bugs and flowers. We made so many fun things out of twigs and leaves!” She describes a gutter in the street where frogs would hatch, her friends and her hunched over and witnessing the miraculous bundles of eggs. “There were weather balloons—we’d pick up those plastic scraps and make things with them. I definitely have a memory of playing with so many different textures and parts of the yard.” Making, repurposing, mixing one medium with another. I’m thrilled to discover that my hunch had been correct: there are certain creative instincts we carry with us from the start.

Stepping Stones

The “Poetree” is at once a space that holds grief and joy, skill and ambition, experienced poets and writers at the beginning of their journey, whether that journey is through a form or a medium or a language itself. It is, in my short history of walking in The Dalles, a prime example of the best kind of yard art. It is unpretentious. It leans into the seasons—political, emotional, or literal —rather than avoiding them. Colleen has added some stepping stones directly before it, a clear invitation for folks to pause and engage with the artwork. Sitting at the top of the display rests a glass bird, which Colleen explains is a reference to her mother, who has “always had a glass bird called ‘the bluebird of happiness.’” It’s clear that the Poetree is both memorial and living document, that it transforms as needed while remaining, always, both. Like the butterfly, it gives readers, neighbors, travelers-on-foot and curious writers the gift of multiple opportunities to experience its quiet potency: no matter how many times I’ve already walked by it, I’m always delighted.