Column: Tumbled glass pieces of wisdom: Let it be. Let it be.

By Nancy Turner

Nancy Turner

When I was learning to read, I began to understand how we use words, as well as art, music, and dance, to evoke an idea or experience. I was fascinated by the fact that when I thought the word ‘orange,’ my mouth salivated. Conjuring images of my cat asleep on my bed made me feel safe. Merely soliciting an image in my mind could change me. As an adult, I continue to be intrigued by this phenomenon. It’s the same with negative or positive thoughts. For better or worse, they influence how we feel.

My family frequently camped along the Clackamas River and on the flanks of Mt. Hood. We boated among the islands of Puget Sound. I learned to love being out in nature. My sisters and I spent hours scanning beaches and streams, filling our pockets with rocks, shells and beach glass. We accumulated, by the jar full, broken shards of glass worn smooth by waves tumbling them against the sand. As a child, I couldn’t explain why I liked them. All I knew was that I wanted something tangible to remind me of the joy I felt when exploring the outdoors. When I grew older, I appreciated those frosted objects as icons to remind me of how I also got broken and tumbled; my rough edges worn away by the abrasions of life.

Smashed and crashed by the waves that make towards the pebbl'd shore, these pieces are finely shaped and smooth to the touch and maybe something more.

My sisters and I grew up and moved away from home, leaving countless jars and metal coffee cans overflowing with our keepsakes. Eventually, Mom tired of storing them. I was in my forties and too busy with family and work to bother with my childhood collection. I told her I didn’t want them. She scattered them across her gravel driveway.

As an adult, I continued to collect treasures. I graduated from pockets to suitcases. On a trip to Bali, I went trolling for gifts to carry home. Inside the central market of Ubon, sweet smoky incense permeated the air, making my eyes water. I shuffled through narrow corridors jam-packed with clothing, paintings, wind chimes and a plethora of tourist trinkets. I bought exotic masks and silk scarves. Feeling satiated and a bit claustrophobic, I searched for an exit. Just when I thought I’d never find the way out, a beam of sunlight illuminated a stall of dusty wood carvings. From behind a Hindu Garuda and a Balinese Barong peered the face of Kwan Yin. The shopkeeper lifted her out and stood the three-foot-tall carving on the floor. Her beauty took my breath away.

For centuries Kwan Yin has been one of the most universally beloved deities of the Buddhist tradition. She is a Bodhisattva who embodies the archetypes the Tibetan goddess, Tara, and of the Christian Virgin Mary. Using the original sense of the term ‘virgin,’ meaning ‘whole unto herself,’ Kwan Yin is a virgin goddess. She is neither owned by her father, a husband, or brother. As the goddess of compassion, she embodies mercy, kindness, tolerance, and love. She is known and revered as, “she who hears the cries of the world.’

One of her hands held a vase from which flows the ‘Water of Life,’ blessing all living beings. Her other hand was raised in the traditional mudra of safety and protection. Typically, a dragon twists around the base of such statues as a symbol of strength and divine power. However, it’s not unusual for religious icons to change from one culture to the next. The Balinese carver had placed her on the back of a porpoise.

I bought the carving of Kwan Yin. The statue was merely a piece of wood chiseled according to the vision of the carver, yet, I knew that every time I looked at it, my mind would evoke a sense of peace.

Years ago, my (then) partner fell while pruning a tree, landing on his back. The doctor at the emergency room said that at any moment a blood clot could dislodge, causing instant death. For hours he lay on the stretcher. X-rays showed a broken neck vertebra. My partner had been a robust, active fellow. His inability to move terrified me. My mood swung from intense compassion for him, with a desire to help him heal, no matter what, to moments of anger, accusing him of causing the accident through arrogant carelessness. I chastised myself for those nasty thoughts, but I couldn’t help thinking them.

After many weeks in the hospital, he gained some nerve sensations and the ability to move his extremities. With a neck and chest brace and a wheelchair, he came home to recover. He struggled, becoming self-absorbed and depressed. I was his only caregiver, providing for all of his basic needs, including transporting him to numerous medical appointments. As a single parent, I continued to go to work and care for my three young children. I grew tired and resentful. Often, I could not imagine enduring another day of subjugating my needs for the well-being of an adult. I became irritable and emotionally distant. It was a rough time for everyone.

One night during that challenging time, I had an amazing dream. The Virgin Mary appeared before me. Her luminous, blue gown ruffled slightly. She stood calmly with both palms open, raised along her sides in a gesture of welcoming inclusion and serenity. She didn’t speak, but I felt her loving presence. I reluctantly woke up and marveled that such a peaceful image had come to me. My inner dream maker had given me a gift that transcended rational thought or words.

My family, with its mix of agnostic, Unitarian, and Quaker heritage, scoffed at religious icons. I’d been raised to see things in a literal, concrete way. However, I found the image of Mary comforting. I spontaneously started humming the Beatles’ song, “When in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me, speaking words of wisdom: Let it be. Let it be.”

That simple yet profound dream endowed me with greater acceptance of others, and of myself. I began to form conscious intentions to be kinder, and to forgive my negative judgements. I relaxed in my role as caregiver. Most significantly, I stopped whipping myself for what I was feeling about my situation. Fear, anger, confusion, and exhaustion became more acceptable and reasonable responses to what I was coping with. I asked for help.

My mother agreed to take my kids for a day so I could have time to myself. For a whole day, they romped outside, climbed trees, and read books with Grandma. They arrive home tired and happy. They had needed the break as much as I had. Their pockets were bulging.

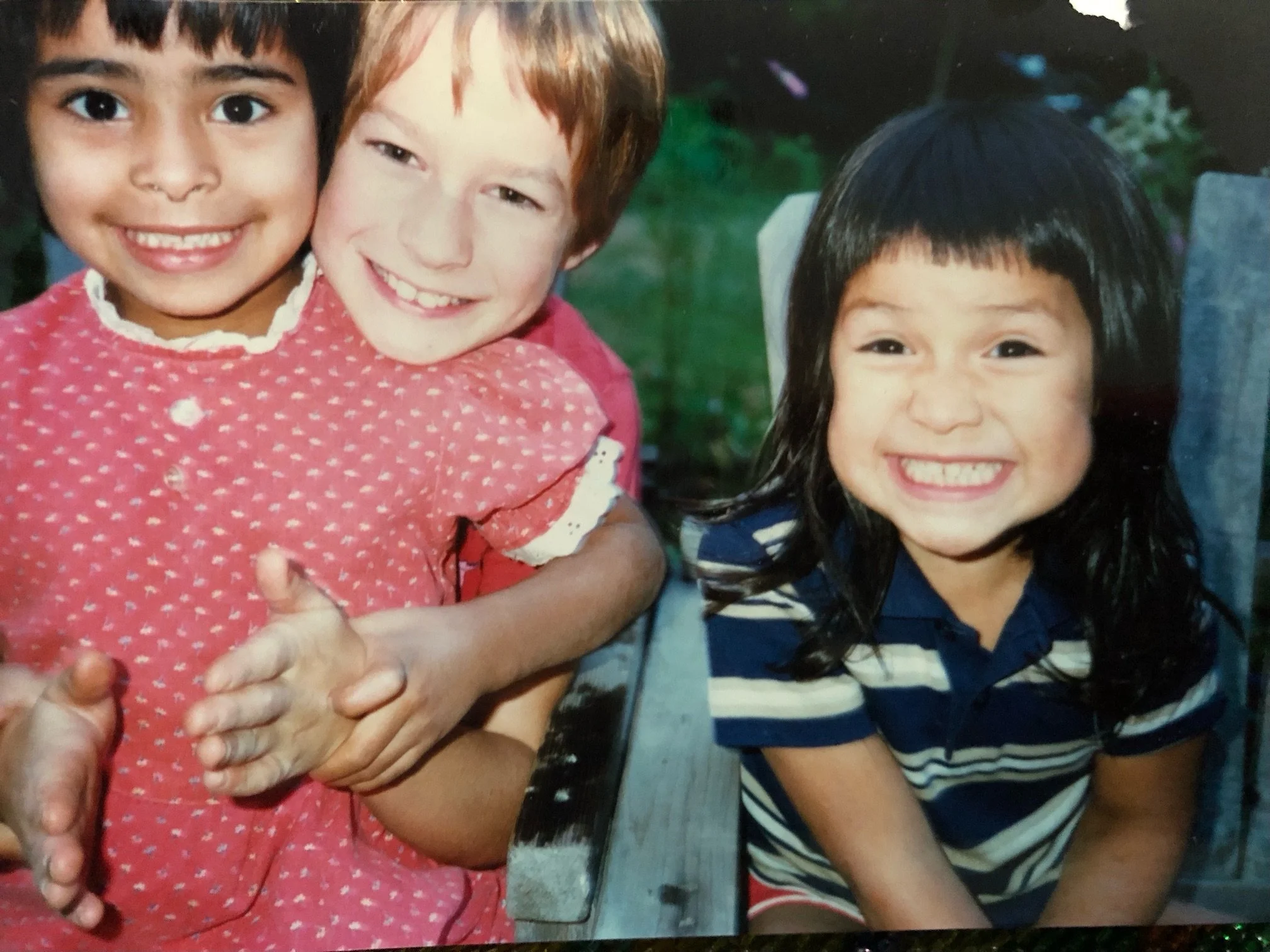

Angela, Toby and Elena

“Look, Mama,” my son, Toby, exclaimed, “I found these beautiful rocks on Grandma’s driveway.” He gently placed handfuls of small stones on the table. My daughters, Angela and Elena, emptied their pockets as well, bringing forth pebbles, broken shells and beach glass. I pretended I’d never seen them before.

Toby was beaming. “I want to keep them forever. Can I have a glass jar? I want to look at them every day. They will remind me to be happy.”

I smiled as I watched my children’s enthusiasm for objects unwittingly passed from one generation to the next. I was glad to store their treasures, just as my mother had done.

In your home you might have an image of Mary, the divine mother of love, or of Tara, the goddess of compassion. My Kwan Yin, along with a figure of Our Lady of Guadalupe that I brought home from Mexico, both stand on a sideboard in my dining room. They are archetypal figures of the tender feminine found in all religions. Every day they are my visual reminders: Be kind. Be compassionate. Love everything. Nothing else matters.

Support Local News

Available to everyone. Funded by readers.